It’s September. Summer in Glasgow has been a mix of short-lived sun, biblical rain and broiling skies. Elsewhere the climate in southern Europe and the aptly named Furnace Creek in Death Valley, California have endured temperatures up to 55 degrees Celsius – 131 degrees Fahrenheit. On social media, tourists to Furnace Creek post selfies standing beside a large thermometer as if it’s some kind of trophy, incognisant of the world’s highest recorded temperatures. That asteroid can’t come soon enough.

Faced with the prospect of being boiled from the inside, one should be grateful for the lure of a cool, dark, cinema. Welcome to hashtag #Barbenheimer, the former being Barbie, a film based on Lilli, a 1950s German strip cartoon character that became the first adult female doll and whose copyright was purchased by Mattel and rebranded as Barbie. Its partner is Oppenheimer, a biopic of J. Robert Oppenheimer, based on the Pulitzer prize-winning book, American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin which recounts the life of the physicist and his role from 1942-46 in the Manhattan Project and the development of the first atomic bomb.

These films are arguably the first to fill the cinemagoing void caused by Covid-19. Even I bought into the hype and pre-booked tickets to Oppenheimer at the local IMAX on the basis it might be the better visual experience. Rarely have I been in an audience comprised mainly of fleece-wearing, rucksack-toting, sensibly-shod males, the majority of whom were either science graduates or impersonating them.

After the film, marred by an undercooked script, a dreadful score and director, Christopher Nolan’s inability to handle female characters, while waiting in an interminable traffic jam at the Science Centre, a depressing thought descended, how it took Mr. Oppenheimer and his colleagues less time to create the atomic bomb than for me to make Tilo in Real Life. It’s a regret I’ve come to own, having started the shoot in August 2018, followed by my injury a year later which necessarily put the project on hold, due my lack of mobility and ongoing lack of confidence.

Were I a protagonist in a film, my hamartia – my internal character flaw – would be a lack of faith in my ability, a wrong-headed notion if ever. That I continue to work on Tilo is a measure of my determination. That, or my own folly. As William Goldman said in Adventures in the Screen Trade, ‘Nobody knows anything,’ adding, ‘Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.’

What I do know is perhaps it’s not the best idea to shoot a film that requires 90% exterior locations in the West coast of Scotland, regardless of the season. In short, it’s the weather, stupid. While making The Devil’s Plantation, in 2008 I returned to Glasgow after living in Edinburgh. It didn’t take long to be reminded of the inclement climate. That summer it rained virtually every day, resulting in me rushing out the door whenever the sun put his hat on, only to be greeted by a sudden downpour in some corner of a scheme or a cemetery. Continuity was out of the question, so many a reshoot was made in pursuit of the film.

Back in the short-lived days of DV filmmaking, when everyone and their dog were supposedly on the street shooting their verité masterpieces, I begged to differ. In theory it was possible to make an entire movie guerrilla-style on a microbudget, but very few ever accomplished it. I soon worked out that, contrary to film wisdom, less is more. Whenever I chance on a film crew in the wild, they come in battalions, most of them surplus and usually kitted out for a polar expedition.

It might be a beautiful lie, but to quote Queen Victoria, ‘Beware of artists. They mix with all classes and are therefore dangerous.’ Indeed, but do you know who’s more dangerous? A lone working-class woman on the street with a camera. Why? Because my superpower, like that of most women my age, is almost complete invisibility. On the rare times I’m approached, its either by hi-vis jacket clad, minimum-waged security staff come to chase me or stray lonely souls who just needed someone to talk to that day.

Two weeks ago, on a bright and breezy Friday evening, I took my chance to shoot a scene for Tilo on a quiet-ish road close to an out-of-town shopping centre, chosen because it has all the elements I need: an ident-free bus shelter with very few passengers and – importantly – equally few abandoned shopping trolleys.

Following two recces to said bus shelter, finally I committed to hauling myself, my camera kit and my lead actor to the location. En route, Tilo rattled in the back of the car, protesting like the adolescent he is. It’s at these moments I realise the absurdity of this exercise, to make a film of ridiculous ambition but with zero resource (again). And so the cliché of who and what a film director does goes out the window, which in my book is healthy.

On arrival, I’m confronted by the sight of not the usual two or three trolleys, but at least twenty. These had to be moved out of shot, apart from one which, after an impromptu casting session based on size, not talent, had just won the role of Tilo’s companion. As I set up, a man arrives; tall and bearded, wearing an outlandish outfit of knee-high boots, black duster coat, green shirt and a wide-brimmed black hat covering his long, lank grey hair, a cross between a radical rabbi and the Lone Groover

To top off the look, in one hand he’s holding a small potted plant, which at one point he shoves in his coat pocket. Though I’m stood directly opposite him, tripod and camera at the ready, he barely registers me. Soon he’s joined by a few other passengers. Nobody pays attention to the two carefully posed artistes behind them at the bus shelter, nor to me. So I wait.

People who don’t know me assume I’m impatient by the way I jump from one idea to the next, or by freely expressing my opinions. The latter point I’ll concede but when it comes to a shoot, I’m as silently stoic as I am persistent. Like a hunter – or karma – I am a patient gangsta. Not through choice, but rather, by necessity over what I can’t control. Existentially I am at one with Tilo and his companion.

On this shoot I am tested. This is entirely a consequence of no-budget, run-n’-gun filmmaking. While Warner Bros only has to roll up to Glasgow’s City Chambers and not only do they get the city centre to play with, causing diversions and headaches for business owners and drivers but also, for reasons unknown they receive £150,000 from the council coffers. My fellow filmmaker, Grant McPhee made several FOIs to Glasgow City Council to confirm this. It’s quite a story.

On this quiet backroad it’s well past 7pm yet the traffic is unrelenting. Buses come and go – part of the scene as storyboarded – as do people, who are not. On the whole, they’re obliging. A few kind folk, on seeing the camera, volunteer to move, unaware they can be digitally painted out. None enquire as to why I’m photographing a bus shelter in the first place. The trolleys, meanwhile remain silent.

Shot by shot, I do as planned. By about 8pm the daylight dims. It’s time to call a wrap. Tilo and his co-star behaved impeccably throughout. The buses came and went and somewhere between the mess of real life and the fabulous fiction I’m creating, I’ve succeeded. We bid goodbye to Tilo’s co-star before I dump the camera kit into the leading actor’s basket back to the car. In the edit, I estimate the scene will occupy 90-100 seconds of screen time. As I leave, I console myself with the thought that regardless of budget, even Warner Bros can’t buy the weather in Scotland.

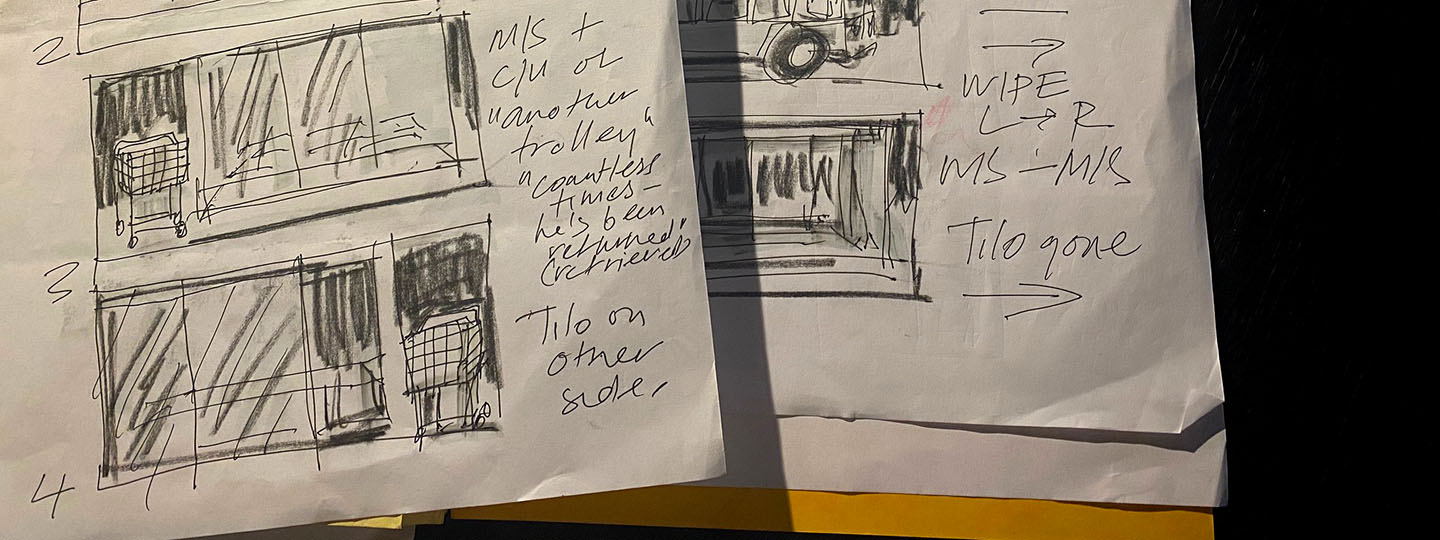

The above image is my scrappy storyboard for the scene described above. As I write this, I’ve only just returned from the bus shelter (for the fifth time) to shoot at night.