As Richard Brody, the New Yorker film critic, says:

Independence isn’t a matter of financing but of urgency. An independent film is one that’s made within the arm’s reach of the filmmaker, that’s experiential - that the filmmaker makes in order to see not just the world at large but also their own place in it.

At some distant point in the mid-20th century at the age of six, maybe seven, I exited the Odeon cinema in Renfield Street, Glasgow, holding my grandmother Lizzie's hand. We had just watched Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl. Dizzy with enchantment, I let go and danced my way into the dark, rainswept street where suddenly Glasgow transformed into New York and I became Fanny Brice. I remember how at that moment I committed my joy to memory, a memory that endures to this day and one that confirms the power of cinema.

Why does anyone make films? Where does the motivation come from? For the 7-year-old me, whose highest aspiration was to get a job in a curtain shop to avoid working in the local biscuit factory it was inconceivable. Today I still remind myself I am a filmmaker and have been for most of my life.

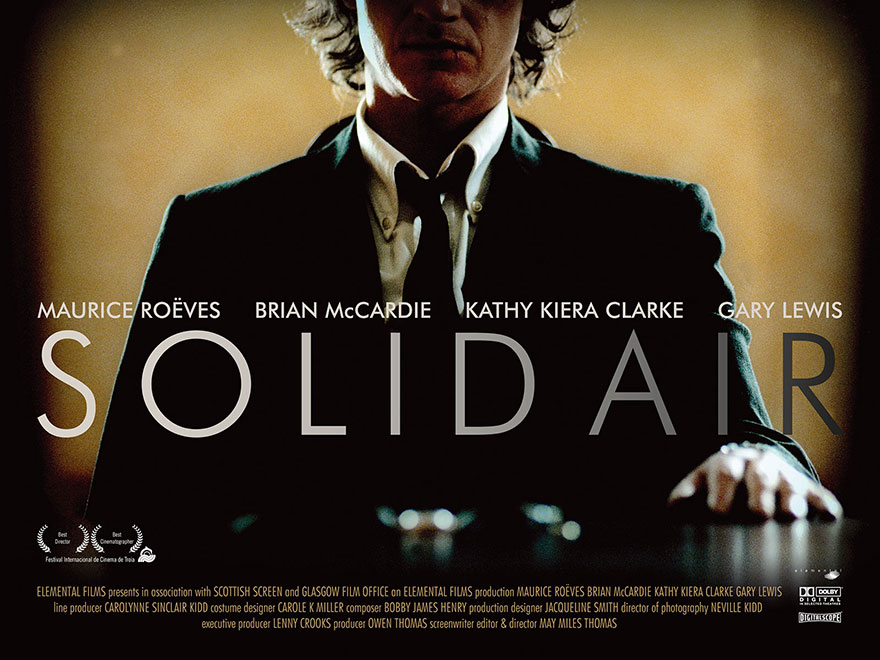

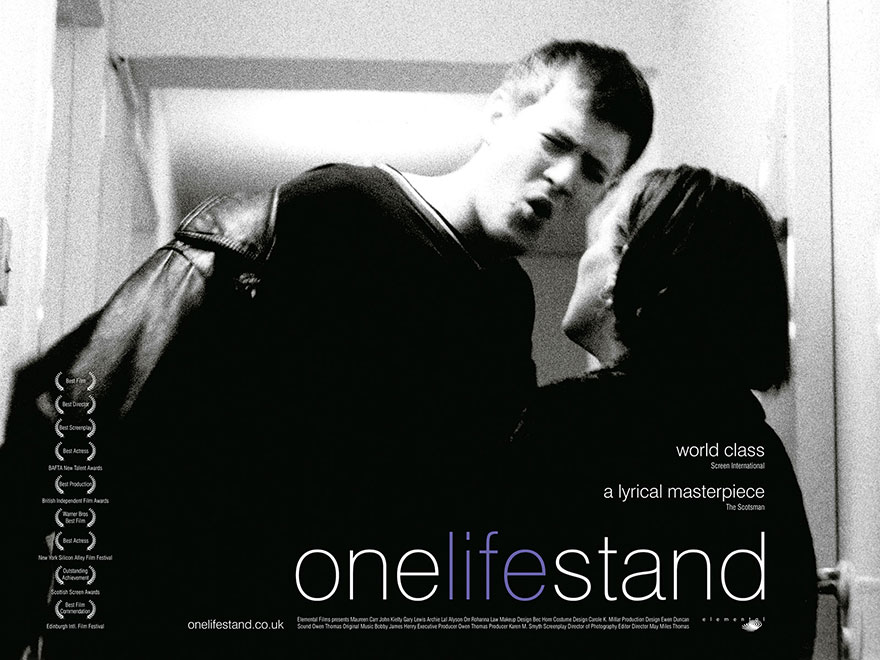

In 1995 I set up Elemental as a place to make my films. Previously I've worked in television, music video and commercials but since 2000 my focus has been on feature-length work. Now I make films using only what's within reach and within my gift with no commercial imperative or desire for the trappings. For me, it's less about mastering a craft than creating a kind of magic.

With each new film I begin again. It's all about story, story and story – to recapture that moment outside the Odeon cinema.

~ May Miles Thomas

...