My husband caught me tapping on my laptop the other night. He asked what I was writing. “A blog post,” I replied, so he said, “Then write something self-affirming, something uplifting.” It doesn’t come easily. It’s over a year since I last posted on this site but on each attempt the words refused to be positive, so I lost heart and pressed delete instead.

On an overcast Friday in early February I’m writing this in my shed. Only I’m not. I’m staring at a set of colour-coded index cards on the wall, each card representing a scene for my ongoing project, Tilo in Real Life. On a shelf, alongside other props, sit three small electrical appliances purchased from eBay who appear as characters in the film, but right now they act as my conscience, taunting me to get back to work. This year, I tell them, this year.

Perhaps it's time I realised the only person who'll grant me permission to finish the film is me. It's time too that I stopped identifying as a frail middle-aged woman and revert to being a filmmaker. The Tilo project has stalled, I believe, because... I won’t lie. Since my accident in July 2019, performing ordinary tasks is like treading molasses. Opioids still cloud my thinking and I am careful how I use the little energy I have.

Here I console myself with the thought - making a film is not an ordinary task. Chronic pain is complex. For instance, I can no longer walk the distance needed to reach the alpha zone that sparks inspiration. There's a loss of confidence, of feeling defeated before I even begin a task. And there's the rarely-discussed psychic low that, coupled with ageing, prompts in me a deep shame borne of inadequacy.

I'm not alone. If there's been any upside to my experience it's to listen to others. Last summer, I took part in an NHS Pain Management Programme. Over ten weeks, via Teams calls, I met with a group of patients, supervised by NHS staff, mainly physiotherapists, psychiatrists and specialist pain nurses. It wasn't an ideal situation to be among strangers gathered to discuss confidential health issues. It struck me too that my fellow patients were all the same age, all white, all female and, by any measure, all working class. Regretably, at the end of the ten weeks I was still in pain and no better equipped to deal with it but it was a humbling exercise to hear others' experiences.

I could lament all day, every day with this poor-me refrain about what my surgeon called the ‘life-limiting’ impact of my injury, but it was only when neighbours and acquaintances began addressing ‘the knee’ instead of me, that I resolved to avoid the subject. Of course, people mean well and it's churlish to criticise but on most days I feel alienated and alone. Maybe it's just the drugs.

It's not that I’m lame or lazy, quite the reverse. I’m working on several projects, all at different stages. Last year I tried writing long-form for the first time, a non-fiction work about my dead sister. Apart from Tilo I also have three potential film projects, one set in the US, the others closer to home.

Fortunately, I’m able to work free from rules, having realised the futility of making films in a conventional way. Indeed, I remember the day I made the decision - 6th October 2014 - when I received a two-line rejection email from Creative Scotland for a funding application for Voyageuse.

By taking money out of the equation I created a space for the film to grow organically. While this way of working was liberating, it was also precarious because when there’s no commercial imperative, no third parties to appease and no deadlines to meet, it’s easy to conjure insurmountable challenges and court defeat. More positively, I had no expectations for the film so every invitation to screen it was a small victory of sorts.

On the downside, there's been no remuneration but there’s not much of a payday on the majority of independent UK films either, particularly short films where aspiring makers cut their teeth. That state-sponsored shorts schemes typically require the cast and crew - tacitly - to work at a reduced rate or for no fees at all is the dirty secret of UK and Scottish filmmaking, which under employment law is very possibly illegal and only reinforces a lack of accessibility to the business. Even on feature-length work, the protracted timescale and cost of developing a project reduces the amount one can earn to minimum-wage levels, assuming one hasn’t had to defer fees, a common practice.

This perhaps explains the dearth of what agencies and funders coyly term, 'those from a low socio-economic background.' The cultural gatekeepers are so invested in diversity and inclusion that being poor is now a characteristic to identify as, as opposed to simply being poor. Either way, it places the lower orders at a disadvantage. I mean, who wants to admit to living in poverty? When V. was rejected for funding, I recall my relief, at no longer having to play the supplicant, to sit up and beg for what was a paltry amount and worse, to have one's work interfered with. In the end, for most of us film is a zero-sum game.

On the upside, by doing everything yourself, there’s no one to fire. The risk however, is that if/when a project falls into an abyss of the maker’s failings, the work itself fails. Or does it? Here I’m in a quandary – can a creative venture fail? Under whose authority can a poem be deemed substandard, a stage play a dud, a novel pulpable and a film a complete stiff? Critics and reviewers are paid to express their views but in the end subjectivity is just code for opinion.

In an era of overcooked hyperbole, even the most modest artistic endeavour is applauded. When quote whores gush on film posters and book covers, I wonder, what is the value of criticism in the face of marketing? Even the most respected and credible film critics are hostage to the press kit and the distributor's junket. 'Endorsement is lazy' - that memorable line from Mad Men - applies to the publicity churn of big-budget, studio-backed films whose stars ARE the celebrities doing the endorsing but I'm perplexed by the marketing of low-budget, niche films. Does a press release really drive audiences into cinemas? With margins so low for independent film, is there a return on investment? Does it matter?

I recall a quote attributed to, of all people, director Oliver Stone's father, who says that writing is 'arse plus seat.' Sitting here, I try to persuade myself the only corrective to my woes is desire coupled with graft but in the meantime arse plus seat will have to do. I remind myself too that so far on Tilo I've already taken on twenty different roles. After all, nobody has one job any longer. Whenever some random is introduced in the media - usually from the creative industries - typically they declare themselves as a multi-hyphenate e.g. 'Daisy is a poet, philosopher, screenwriter and stand-up comedian,' a claim that can be construed either as over-achievement or a great big fib. In the course of making a film I assume so many roles, it makes Daisy look like a lazy besom.

For example, recently I had a request from the BFI Film and Television Archive because they’re interested in a film I made with my husband in 1999, Colentina, a glorified home movie about his family, and a test for a prototype non-linear edit system we acquired while living in Berlin in the late 1990s. At that time, the BFI very kindly restored several reels of 16mm shot between 1929 and the mid-1950s by my husband’s grandparents. The restoration took two years and today the original films - the Eisner Collection - are kept in their archive.

That the BFI wants to make the film available in UK libraries and on their streaming platform is gratifying but when I sat down to watch it, I cringed at the image quality (MiniDV up-ressed to HD on Teranex but ungraded) and the sound which, though gilded with some very expensive music, was as basic as a brick. Fortunately I didn’t think twice about how to salvage it since I’m fairly proficient at what are highly specialised, technical jobs. If I wasn’t, I estimated that a colour grade, sound design and final mix would cost not less than 10 grand, probably more. Either way, it’s money I don’t have, and money that the BFI would certainly never spend – indeed, they’re getting Colentina for free - but I had the satisfaction of doing the work myself.

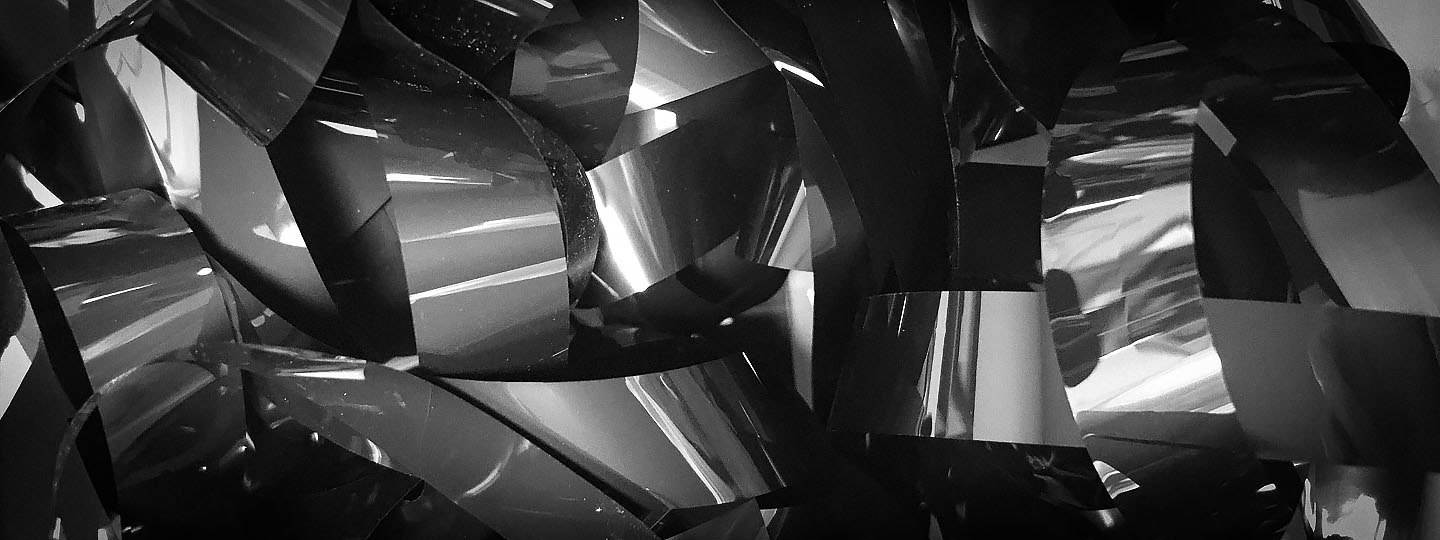

Will I complete Tilo? I hope so. Meanwhile in the shed I notice boxes of old VHS tapes which, like the three appliances, were purchased as props for the film. There's something very levelling about the sight of these films, the many millions they cost to produce, the thousands of people who create them, the hundreds of stories they tell, reduced to an outmoded format, a spool of magnetic tape encased in a plastic shell, unseen and unwanted. It's a reminder that, if I'm going to self-ID as a filmmaker this year, then I need to remind myself of just how privileged I am.

The above image is of video tape. I used an axe to break into the casing and unspooled the reel. I only have half a notion why I needed a hundred or more old VHS tapes for the film but I'm sure the answer will come.