Recently I hosted a Q&A at the CCA Glasgow for the makers of Far from the Apple Tree, an ambitious supernatural thriller with a nod to the 1970s English horror genre. Shot over 12 days using multiple formats that required building a bespoke film lab, it’s an amazing achievement.

Rarely do I attend such events but I wanted to applaud the film’s makers, Grant McPhee, Olivia Gifford, Steven Moore and Ben Soper, as well as the cast and crew who came to the screening. The film’s director, Grant is also a leading light of Year Zero/Tartan Features, a group of Scottish independent filmmakers who produce films with little industry or institutional support so naturally I’m simpatico with their cause. Here’s a link to Grant’s blog which offers a great insight into the process.

After the Q&A I wondered – could Apple Tree or any other indie film be improved with more money? Of course the question’s moot because the film already exists. But who’s to say what demands might have been made on the makers in exchange for largesse?

In my own past dealings with funders I’ve been asked to alter scripts in ways that are, frankly, idiotic, from dropping essential characters to changing the period and location of a story for no logical reason other than to meet fuzzy bureaucratic whims. Of course, entering a contract with any backer means compromise but it also speaks to a culture of risk aversion that saps the life out of originality. As much as I’d love a payday I’d sooner cleave to my creative automony and take my chances on the margins.

At the Q&A I spoke about why independent film matters. At best, when a development executive offers notes, it suggests they’re in possession of a magic formula that guarantees success when in reality no such thing exists. If it did I’d be filling my boots along with every other filmmaker. At worst – and I hear this constantly – heavy-handed oversight speaks to a lack of faith, that somehow the makers can’t be trusted to get it right.

True or not, it begs the question – if a project’s so flawed that it requires fifteen drafts then why support it? The kind of films I want to make are PRECISELY those that no one will fund because I don’t want to make safe, formulaic films on the cheap, i.e. a typical Scottish budget when Hollywood does it so much better. To lead a large cast and crew in pursuit of a standard romcom or realist drama is my idea of hell.

In the case of Apple Tree, I don’t think more resource would have resulted in a better film. No film is ever perfect because no filmmaker is. The best the makers can hope for is to achieve or surpass their original intentions. Indeed, given the current interest in all things hauntology, Apple Tree is well-placed to reach an audience, as I witnessed during the Glasgow Film Festival where I saw the Swedish hypno-thriller, Black Circle, a micro-budget film of a similar stripe that filled the GFT’s largest screen. Clearly there’s an appetite for these films and an audience eager for an alternative to the multiplex mush so I wish Apple Tree every success.

Where public funding could be useful is at the other end of the production process where, once made, films can be supported to help reach an audience – from PR and marketing to the cost of a train fare or a night in a hotel. This is especially true for films made on micro budgets by people passionate about getting their stories told and their craft. Most indies never achieve meaningful distribution, be it theatrical or online because the budget’s already been blown on production. Even those that secure a release are buried under the sheer weight of numbers.

The same is true of the festival circuit where too many films compete for slots on the A&B-list circuit while the rest expect the makers to pay their own way to a) submit and b) attend. Increasingly I’m seeing crowdfunders set up solely to meet the cost of festival submissions which for features can be as much as £100 a pop. If public funding bodies are prepared to subsidise film production then surely it’s reasonable to directly subsidise filmmakers who show initiative by making films without state support? The difficulty with this scenario, however, is the question of quality and who gets to decide which films are worthy of support.

I was reminded of this when I was contacted recently by the very friendly Digital Communications Officer at Screen Scotland regarding a possible web feature about my work. Her email offered three options – new work, recent work and my career in general.

In truth I’ve hesitated over how to respond. My latest film, TIRL is at too early a stage. Voyageuse is currently in limbo, with no further screenings planned and, frustratingly, no contact from those who previously expressed an interest. The third suggestion, to talk about my ‘filmmaking achievements’ I’m mulling over because genuinely I’m at a loss for what to say. Perhaps I should apply for funding to hire a publicist…

Meanwhile I can be found on the streets of Glasgow where lately I’ve seen things that, frankly, if I showed them in a film, no one would believe it. And I’m not even making a horror. Real life, innit?

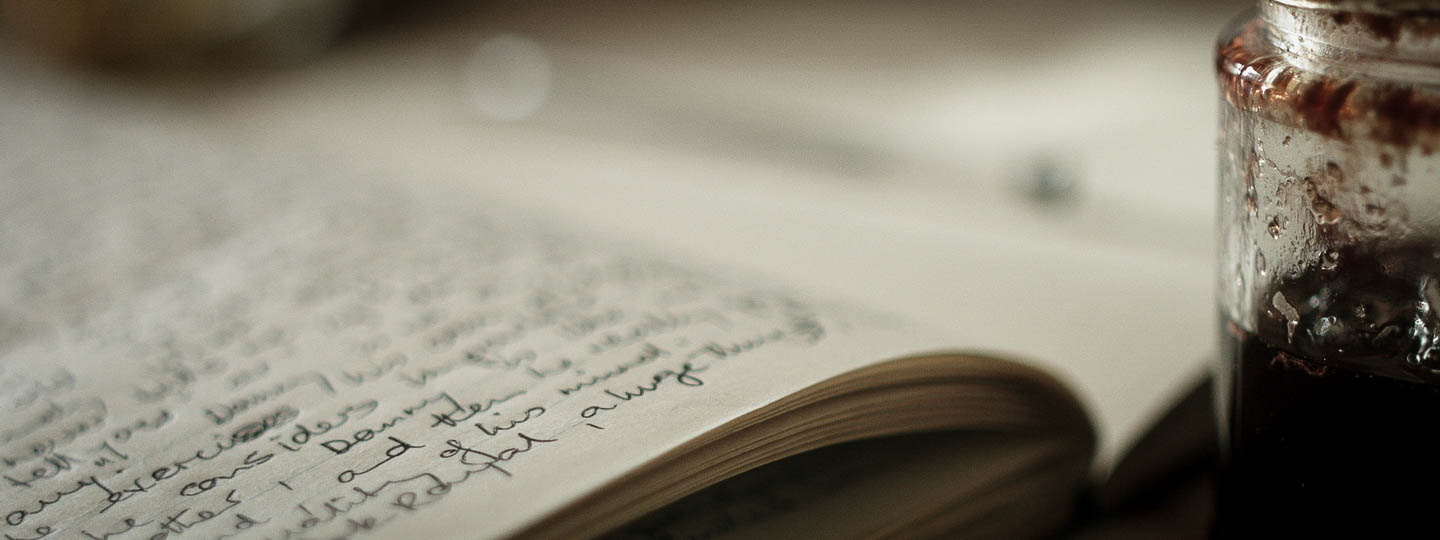

The above image is a frame grab from Voyageuse showing one of Erica’s notebooks.